JNI Performance - The Saga continues

While I did benchmark the native transport of Netty I noticed the performance of gathering writes was not quite what I had expected.

Use

Let me welcome you to the dark side!

There are a few techniques you can use to improve the performance. These sections will cover them…

Caching jmethodID, jfieldID and jclass

When you work with JNI you often need to either access a method of a java object (jobject) or a field which holds some value.

Also, you often need to get the class (jclass) to instantiate a new Object and return it from within your JNI call. All of this means you will need to make a "lookup" to get access to the needed jmethodID, jfieldID or jclass. But this doesn't come for free. Each lookup takes time and so affects performance if you are kicking the tires hard enough.

Luckily enough, there is a solution: caching.

Caching of jmethodID and jfieldID is straight forward. All you need to do is lookup the jmethodID or jfieldID and store it in a global field.

jmethodID limitMethodId;

jfieldID limitFieldId;

// Is automatically called once the native code is loaded via System.loadLibary(...);

jint JNI_OnLoad(JavaVM* vm, void* reserved) {

JNIEnv* env;

if ((*vm)->GetEnv(vm, (void **) &env, JNI_VERSION_1_6) != JNI_OK) {

return JNI_ERR;

} else {

jclass cls = (*env)->FindClass("java/nio/Buffer");

// Get the id of the Buffer.limit() method.

limitMethodId = (*env)->GetMethodID(env, cls, "limit", "()I");

// Get int limit field of Buffer

limitFieldId = (*env)->GetFieldID(env, cls, "limit", "I");

}

}

This way, every time you need to either access the field or the method you can just reuse the global jmethodID and jfieldID. This is safe even from different threads. You may be tempted to do the same with jclass, and it may work at first, but then bombs out later. This is because jclass is handled as a local reference and so can be recycled by the GC.

There is a solution, however, which will allow you to cache the jclass and eliminate subsequent lookups. JNI provides special methods to "convert" a local reference to a global one which is guaranteered to not be GC'ed until it is explicitly removed. For example:

jclass bufferCls;

// Is automatically called once the native code is loaded via System.loadLibary(...);

jint JNI_OnLoad(JavaVM* vm, void* reserved) {

JNIEnv* env;

if ((*vm)->GetEnv(vm, (void **) &env, JNI_VERSION_1_6) != JNI_OK) {

return JNI_ERR;

} else {

jclass localBufferCls = (*env)->FindClass(env, "java/nio/ByteBuffer");

bufferCls = (jclass) (*env)->NewGlobalRef(env, localBufferCls);

}

}

// Is automatically called once the Classloader is destroyed

void JNI_OnUnload(JavaVM *vm, void *reserved) {

JNIEnv* env;

if ((*vm)->GetEnv(vm, (void **) &env, JNI_VERSION_1_6) != JNI_OK) {

// Something is wrong but nothing we can do about this :(

return;

} else {

// delete global references so the GC can collect them

if (bufferCls != NULL) {

(*env)->DeleteGlobalRef(env, bufferCls);

}

}

}

Please note the explicit free of the global reference by calling `DeleteGlobalRef(…). This is needed to prevent a memory leak as the GC is not allowed to release it. So remember this!

Crossing the borders

Typically, you have some native code which calls from java into your C code, but there are sometimes also situations where you need to access some data from your C (JNI) code that is stored in the java object itself. For this, you can call "back" into java from within the C code. One problem that is often overlooked is the performance hit it takes to cross the border. This is especially true when you call back from C into java.

The same problem hit me hard when I implemented the writev method of my native transport. This method basically takes an array of ByteBuffer objects and tries to write them via gathering writes for performances reasons. My first approach was to lookup the ByteBuffer.limit() and ByteBuffer.position() methods and cache their `jmethodID's as explained before. This yielded the following:

JNIEXPORT jlong JNICALL Java_io_netty_jni_internal_Native_writev(JNIEnv * env, jclass clazz, jint fd, jobjectArray buffers, jint offset, jint length) {

struct iovec iov[length];

int i;

int iovidx = 0;

for (i = offset; i < length; i++) {

jobject bufObj = (*env)->GetObjectArrayElement(env, buffers, i);

jint pos = (*env)->CallIntMethod(env, bufObj, posId, NULL);

jint limit = (*env)->CallIntMethod(env, bufObj, limitId, NULL);

void *buffer = (*env)->GetDirectBufferAddress(env, bufObj);

iov[iovidx].iov_base = buffer + pos;

iov[iovidx].iov_len = limit - pos;

iovidx++;

}

...

// code to write to the fd

...

}

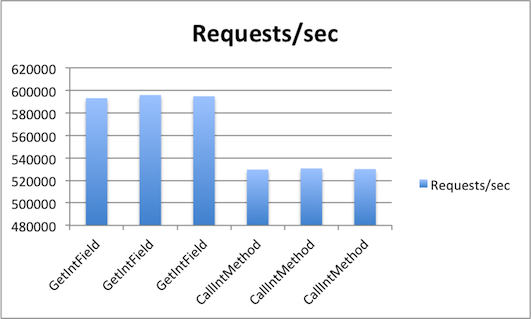

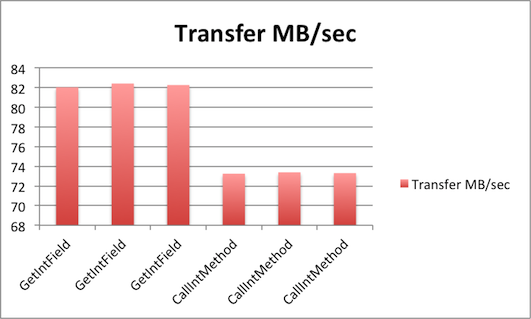

After the first benchmark, I was wondering why the speed was not matching my expections. I was only able to get about 530k req/sec with the following command against my webserver implementation:

# wrk-pipeline -H 'Host: localhost' -H 'Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8' -H 'Connection: keep-alive' -d 120 -c 256 -t 8 --pipeline 16 http://127.0.0.1:8080/plaintext

After more thinking, I suspected that calling back into java code so often during the loop was the cause of the problems. So I checked the openjdk source code to find the names of the actual fields that hold the limit and position values. I changed my code as follows:

JNIEXPORT jlong JNICALL Java_io_netty_jni_internal_Native_writev(JNIEnv * env, jclass clazz, jint fd, jobjectArray buffers, jint offset, jint length) {

struct iovec iov[length];

int i;

int iovidx = 0;

for (i = offset; i < length; i++) {

jobject bufObj = (*env)->GetObjectArrayElement(env, buffers, i);

jint pos = (*env)->GetIntField(env, bufObj, posFieldId);

jint limit = (*env)->GetIntField(env, bufObj, limitFieldId);

void *buffer = (*env)->GetDirectBufferAddress(env, bufObj);

iov[iovidx].iov_base = buffer + pos;

iov[iovidx].iov_len = limit - pos;

iovidx++;

}

...

// code to write to the fd

...

}

This change resulted in a boost of about 63k req/sec for a total of about 593k req/sec! Not bad at all…

Each benchmark iteration included a 20 minute warmup period followed by 3 runs of 2 minutes to gather the actual data.

The following graphs show the outcome in detail:

Lessons learned here are that crossing the border is quite expensive when you are pushing hard enough. The down-side of accessing the fields directly is that a change to the field itself will break your code. In the actual code (which I will blog about and release soon), this is handled gracefully by falling back to using the methods if the fields aren't found, and logging a warning.

Releasing with care

When using JNI, you often have to convert from some of the various j*Array instances to a pointer and release it again after you are done. So make sure all the changes are "synced" between the array you passed to the jni method and the pointer you used within the jni code.

When calling Release*ArrayElements(...) you have to specify a mode to tell the JVM how it should handle the syncing of the array you passed in and the one used within your JNI code.

Different modes are:

-

0

Default: copy everything from the native array to the java array, and free the java array.

-

JNI_ABORT

Don't touch the java array but free it.

-

JNI_COMMIT

Copy everything from the native array to the java array, but don't free it. It must be freed later.

Often people just use mode 0 as it is the "safest". But using 0 when you actually don't need it gives you a performance penality. Why? Mainly because using 0 will trigger an array copy all the time, but there are two situations where you won't need the array copy at all:

- You are not changing the values in the array at all; only reading them.

- The JVM returns a direct pointer to the java array which is pinned in memory. When this is the case, you won't need to copy the array over as you operate directly on the same data used by java itself. Whether or not the JVM does this depends on the JNI implementation. Because of this, you need to pass in a pointer to a jboolean when you obtain the elements. The value of this jboolean indicates whether a copy was made or if it is just pinned.

The following code modifies the native array and then checks if it needs to copy the data back or not.

JNIEXPORT jint JNICALL Java_io_netty_jni_internal_Native_epollWait(JNIEnv * env, jclass clazz, jint efd, jlongArray events, jint timeout) {

int len = (*env)->GetArrayLength(env, events);

struct epoll_event ev[len];

int ready;

// blocks until ev is filled and return if ready < 1.

....

jboolean isCopy;

jlong *elements = (*env)->GetLongArrayElements(env, events, &isCopy);

if (elements == NULL) {

// No memory left ?!?!?

throwOutOfMemoryError(env, "Can't allocate memory");

return return -1;

}

int i;

for (i = 0; i < ready; i++) {

elements[i] = ev[i].data.u64;

}

jint mode;

// release again to prevent memory leak

if (isCopy) {

mode = 0;

} else {

// was just pinned so use JNI_ABORT to eliminate not needed copy.

mode = JNI_ABORT;

}

(*env)->ReleaseLongArrayElements(env, events, elements, mode);

return ready;

}

Doing the isCopy check may save you an array copy, so it's a good practice. There are more JNI methods that allow you to specify a mode, for which this advice also applies.

Summary

Hopefully, this post gave you some insight about JNI and the performance impact some operations have. The next post will cover the native transport for netty in detail, and give you some concrete numbers in terms of performance. So stay tuned ….

Thanks again to Nitsan Wakart , Michael Nitschinger and Jim Crossley for the review!